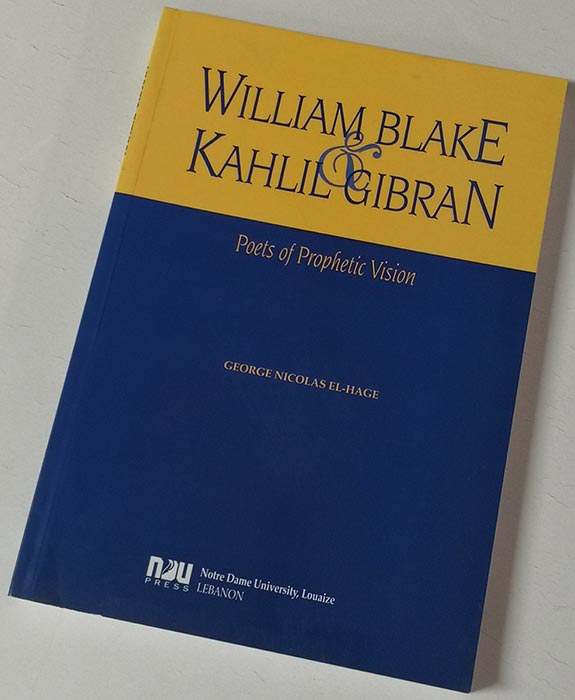

William Blake and Kahlil Gibran ‘Poets of Prophetic Vision’

$ 11.30

William Blake and Kahlil Gibran ‘Poets of Prophetic Vision’ by George Nicolas El-Hage. Notre Dame University, Louaize, Lebanon – Book size: 24 x 17 cm – 171 pages.

- Description

- Shipping & Return

Description

William Blake and Kahlil Gibran ‘Poets of Prophetic Vision’ by George Nicolas El-Hage

Notre Dame University, Louaize, Lebanon

Book size: 24 x 17 cm – 171 pages

Table of contents

Foreword – Dr. Boulos A. Sarru

Acknowledgments

Author’s Introduction

Chapter I – “A Mental Prince” or ” A Child of Light”

Chapter II – The Buds that will Blossom

Chapter III – New Vision

Chapter IV – A More Fertile and Daring Creator.

Chapter V – The God-man and the Antichrist

Selected Biography

Foreword:

We are all prophets by instinct, either in the way of proclaiming a prophecy or in accepting it; there is something intriguing in it that lures our pride to play God, and, when tempered by modesty, or fear, to harbor it in our holy of holies. From Adam to tomorrow the prophetic will always inform our thoughts, sentiments, and actions. Are we not beings in the making hurling ourselves into a status we wish to have? Even when we cower before the challenge of becoming and retreat into the false safety of fixism, our escape underlies our failure to grasp the prophetic.

The present study of William Blake and Gibran K. Gibran: Poets of Prophetic Vision by Professor George Nicholas el-Hage is a vocal proclamation of the nature and role of prophecy. A poet in his own right. Dr. Hage focuses his study on two renowned poets: the first, William Blake, is a forerunner of the Romantic Movement in England; the second, the Lebanese Gibran K. Gibran, is, by all critical acclaim, the author laureate of Oriental romanticism. What the two men shared is not to be resolved or determined in a study of influence or literary indebtedness, but to be assessed in terms of the acute prophetic vision which they both had. Though Dr. Hage, as a scholar and critic, addresses the issue of influence which Blake might have had on Gibran, he does not allow his argument to be overshadowed by critical opinion and historical data of similarities and contrast; he, very effectively, plays the role of a medium between the two poets to have a clairvoyant’s knowledge of three concerns: first, the nature of prophecy in each poet; second, the scope of the prophetic common grounds; and third, the realization of the prophetic vision.

Steering away from a conventional critical summary of the work at hand, I see that the prophetic vision is more possible in romanticism than in classicism; the first is vibrant, rebellious, and ambitious, the second is contained, measured, and decorously conservative. Whether the prophecy projects the future of the present, or a future opposite to the present, it is imperative that it begins in the real present and works its way to that which will be. The impact of the prophecy will be either to carry the recipients into its own realm, thus affecting its fulfillment, or to fail its purpose. The success or failure of the prophecy has no bearing on its essence; it is the failure of the recipient, and inadvertently of the Herald.

William Blake envisioned a world of the ingredients of four zoas of body and spirit to outbalance the four elements of matter constituting the visible world of experience. And thought the paradox of innocence and experience seems inviting, Blake did not fall for the simplicity of the obvious frame of reference. In a sense, he acknowledges the materiality of the world – which is the tangible reality of the vision – to go from it to the transcendent.

Gibran, in turn, was neither alien to Blake’s vision nor, most importantly, to his own. The Lebanese Brahmin was frustrated with a world of “hypocrisy, corruption, and falsehood”; but he was not intimidated by it. Even in the thunderous storms of the early works – gracefully analyzed by Dr. Hage – the serenity of the prophetic vision is clearly manifest. The ugliness of priestcraft is undermined by the beauty of God’s beautiful world; the suppression of the tyrant is foiled by divine mercy and compassion. This positive vision is imperative, hence prophetic.

The vision is by necessity transcendent, but not necessarily an immediate transformation of the base into noble, or a mere bestowing of an “above” value on a “below” object as initial transcendentalism is. The transcendent value is entrenched in the base real and rendered positive and accessible via imagination. Imagination is the alembic of the prophetic vision as it provides this vision with the tools and catalysts of formation and transformation. More so, the imagination is an accessible venue for the knowing soul to express herself through the mediums of image, color, and myth. The active soul, envisioning a world seen only by her, communicates this vision through imagination. Through this communication of prophecy, the imagination is the artist’s tool hopeful of awakening the receiving souls to the vision. Once these receiving souls become “in vision” of “the vision” the prophecy is realized.

Gibran read Blake and discovered his affinities with the English bard, discovered that he had already had his vision. And he had confessed: his second reading and a real understanding of Blake made him more aware of this vision. This awareness, unshared by the multitudes and unreached by the skeptics and the “realists,” placed the two men, like many others who tread the path of vision, on a plane different, unorthodox, and “mad.” And if the two men were labeled mad, it is to their credit then otherwise. After all, are not “all great things touched with madness,” to use Herman Melville’s assertion? Or is not madness in art and act of creation? I hail Blake’s and Gibran’s prophetic vision, and Dr. Hage’s controlled madness.

Boulos A Sarru’, PhD

Professor of English and American Studies, Dean of Humanities, Notre-Dame University, Lebanon, July 10, 2002

a. View or Modify What is in Your Shopping Cart.

When in the Shopping Cart area of the site you can view or modify what is in your shopping cart at any time by clicking on the Add More Items/Refresh Totals button along the bottom of your screen.

b. Checking Out and pay for your purchases online.

When you have finished viewing and wish to end your shopping and pay for the items you have selected, click on the Pay & Finish button at the bottom of your screen.

You will be led through a series of secure ordering procedures and will be asked to fill in personal, shipping and payment option information. When this is completed, you will press the Submit Secure Checkout button and your order will be transmitted to LebanonPostcard for fulfillment.

Absolutely not! Right up until the point why you are asked to review the order information you have given us and if it is correct to click on the final Submit Secure Order button, you can abort the order.

If you don't press the Submit Secure Order button then no order information is transmitted to us.

a. Payment by Credit Card

We accept American Express, MasterCard, Visa, Discover, PayPal... etc... for online payments through 2CheckOut.com. Also, arrangements can be made for bank draft and certified check payments by regular post.

b. Payment by Bank Draft and Certified Check

If you would prefer to pay for your purchases by mail, then you have to contact us first so we can give you our account information.

c. We accept as well payment through WesternUnion, RIA, OMT, BOB Finance, Whish Money.

All prices include shipping and handling. LebanonPostcard will be responsible for sending the packages you order, at your charge, through the service D.H.L. / E.M.S. with tracking number code guaranteeing reception of the package.

We ship as soon as possible, but within maximum 4 days after the order is received.

Credit cards are not charged until we actually ship the items. The items may take between one and six days to arrive, according to the country they are sent to.

Packages are sent with track code to guarantee reception, and delay is rare. In the event of non-delivery or delay, nothing can be done for 7 days. At the end of this period, on our being informed, a demand will be made for the package to be traced. If 14 days after the first dispatch there is still no delivery, a second package will be sent free.

Packages inside Lebanon are sent registered through LibanPost to guarantee reception, and delay or non-delivery is rare. In the event of non-delivery, nothing can be done for 6 days. At the end of this period, on our being informed, a demand will be made to LibanPost for the package to be traced. If 12 days after the first dispatch there is still no delivery, a second package will be sent free.

We ship anywhere in the world. Zones and countries we ship to

Yes. You can cancel you order when you receive an email from us confirming your order, you can reply by canceling it.