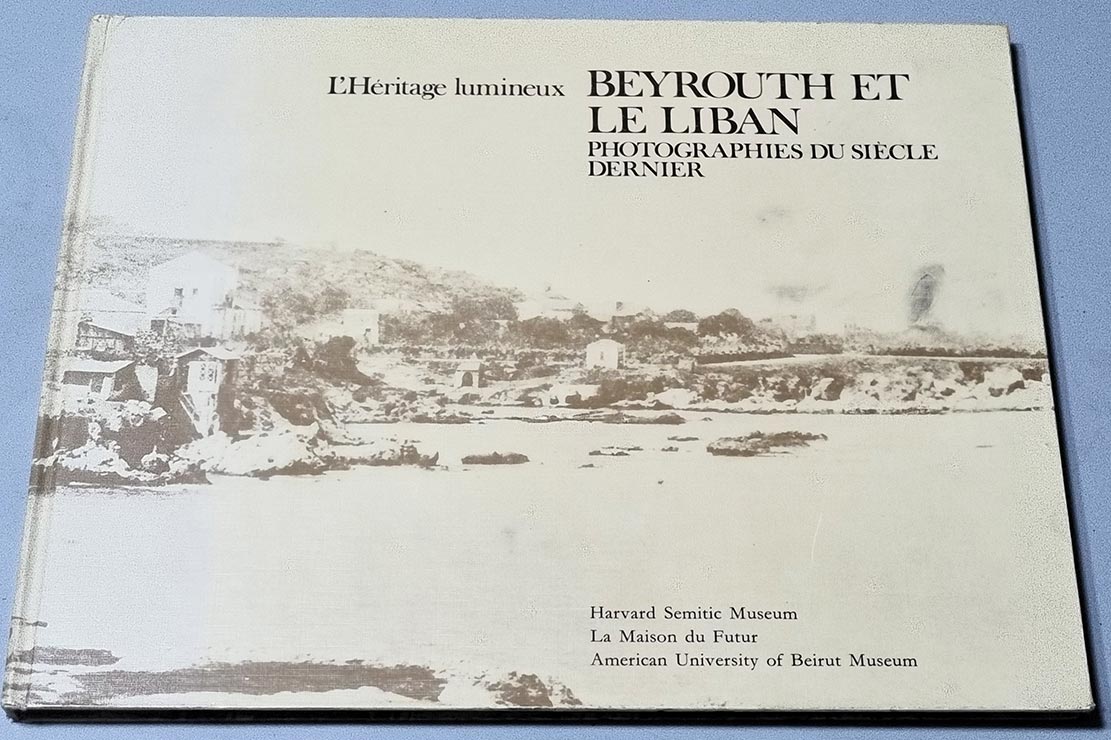

Livre L’Heritage Lumineux – Beyrouth et le Liban – Photographies du Siècle dernier.

L’Heritage Lumineux

$118.00

Description

LebanonPostcard présente le Livre L’Heritage Lumineux – Beyrouth et le Liban – Photographies du Siècle dernier.

Harvard Semitic Museum – La Maison du Futur – American University of Beirut Museum – Hardcover book, 29×23 cm, 76 pages, in French, English and Arabic.

Introduction:

Lebanon’s name salutes the country’s uniquely dazzling appearance. From the earliest writings, the same ancient Semitic root (LBN) seems to have referred both to milky-whiteness and this bright land of snowy peaks so that linguistic archaeologists cannot determine which meaning came first.

Recently, flames and thick black clouds of smoke have obscured mankind’s vision of this land whose fabled beauty has for millennia inspired songs of poets recounting the mythical origins of Europe and romantic landscapes by artists depicting the setting of Adonis’ herds and loves.

As television signals transmitted instantly by satellite bring flickering images of devastation and struggle to the remotest corners of our globe, the need to look afresh at Lebanon through the rediscovered oldest accurate pictures transcends nostalgic curiosity. Camera pioneers were able to record more than those beauties which had attracted the makers of mosaics, tapestries, and engravings. Early photographers’ lenses captured rays of sunlight during the last century which can steadily transmit to us today and tomorrow incontrovertible evidence of industry, skills, agricultural prosperity, urban vitality, the flourishing of religious activity, and cosmopolitan commerce- that perennial heritage and basic environment of Lebanese life which must be recognized, treasured, and re-asserted within the country and throughout the world.

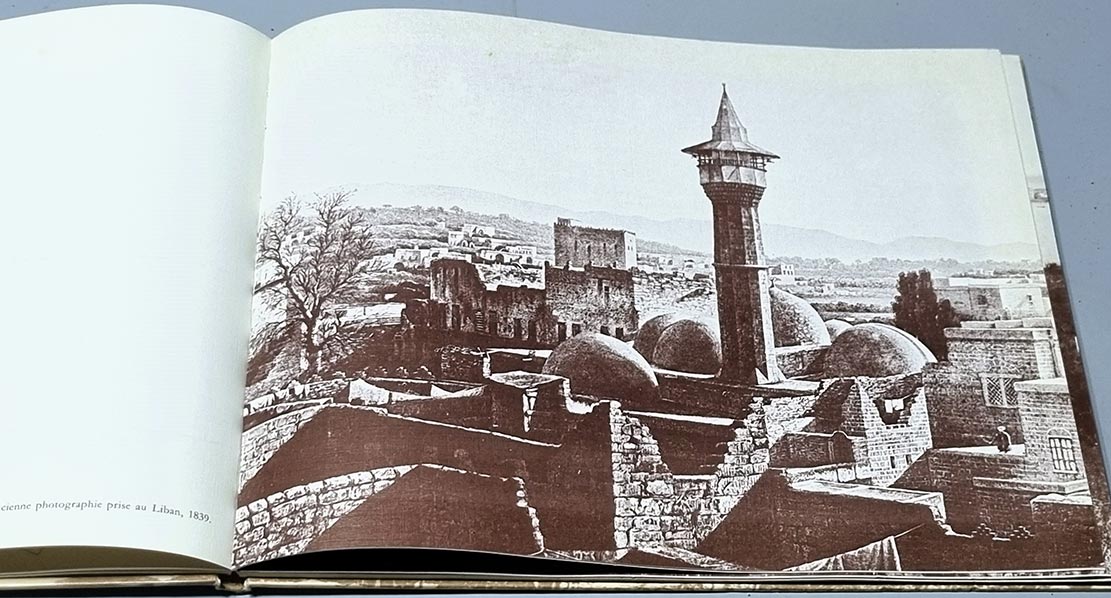

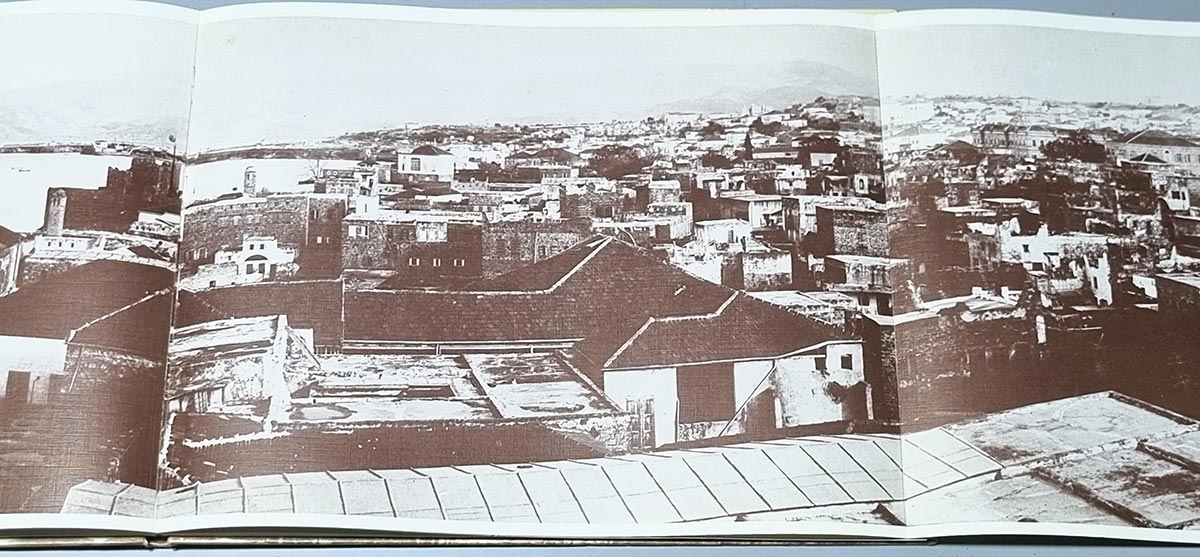

The image (plate 1) which can be considered the first photograph of Lebanon utilizes the traditional skills of the copperplate engrave to clarify and share the results of a revolutionary technique patented by Daguerre in 1839. Each Daguerreotype was a shiny metal plate on which rays of sunlight had been captured through a lens in such a way that a delicate pattern could be discerned after the plate was treated with (poisonous) mercury fumes. Within weeks of the announcement of Daguerre’s invention, N.P. Lerebours, a Parisian maker of optical instruments, dispatched artists and writers equipped with his own version of Daguerreotype kits to record the Near East.

As the metallic light pictures returned to Paris, Lerebours commissioned his engravers to make clichés from which he published reproductions in instalments as Excursions Daguerriennes Vues et Monuments les plus Remarquables du Globe. F. Goupil, one of Lerebours’ light-capturers, describes his picture of Beirut:

“This plate’s view is taken from the terrace of the French consulate and shows the domes of that mosque called after the palace (Jami’ as-Saraya). In the background, you can see in the distance country houses which make a stay in this land an utter delight. Leaving the city you find more than 300 such villas which stretch out a long way towards the mountains through the most enthralling landscape. Most of those pretty villas,… have been adorned with orchards, full of orange trees, pear trees, olive trees, etc. Throughout the mountains, the mulberry tree is particularly cultivated for the silk industry. Majestic Lebanon, peaks covered with snow in winter, extends its ridges – on one side as far as that promontory beyond which lies Tripoli, on the other side as far as Ras el-Abiyad…”

(from Excursions Daguerriennes, Paris, Lerebours, 1842, No. 57)

Goupil’s sensitive remarks also recount other special qualities of life he encountered during this first photographic expedition to Lebanon notably hospitality, story-telling, songs, cuisine, commercial panache, and sincere piety.

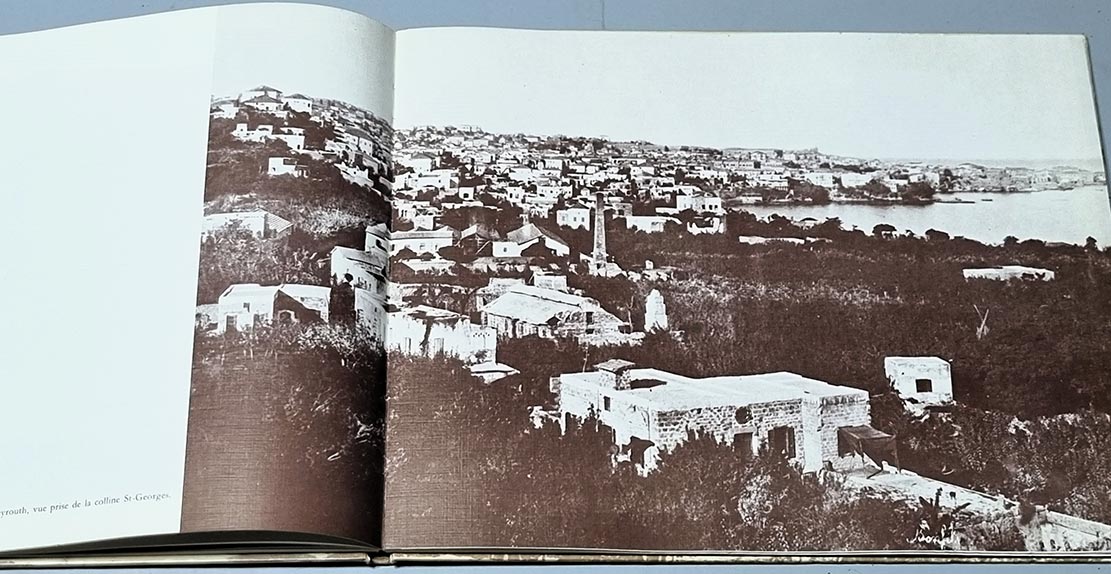

Through a variety of experiments, (including negatives first of paper and eventually of glass plates), camera techniques developed steadily over the next two decades so that many travellers were able to record pictorially their visits to Lebanon. Notably by 1860, Trancrède Dumas had established a photographic studio in Beirut from which he set out on expeditions to depict ancient monuments and cities throughout the Levant. His achievements and those of other, almost forgotten, pioneers are currently being studied by Fouad Debbas for presentation in a comprehensive survey of early photography in Lebanon.

Here, the Harvard Semitic Museum has chosen to concentrate on gold-toned albumen prints produced (with a few anonymous exceptions) by the Bonfils family which came from the Languedoc in 1867 to make Beirut their home and their base for a 50-year-long photographic expedition.

Bonfils photographs permit meticulous study today. Félix Bonfils (1831-1885) reported his methods to colleagues in Paris in 1871, in such a way that we can discern from his careful chemical formulas and the admission that heat caused him much difficulty that the wet plate techniques he was using were still partially in an experimental stage. Later the family was to proudly proclaim that “our views are known throughout the whole world and are justly appreciated for their perfect execution and their permanence.”

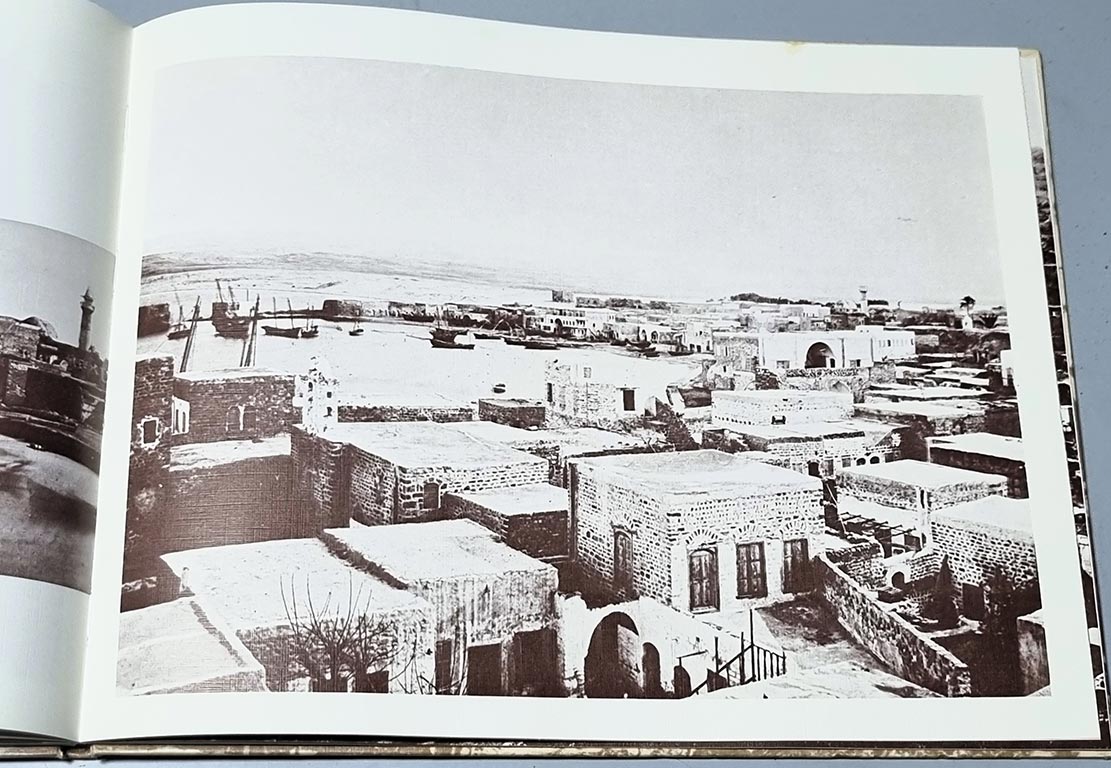

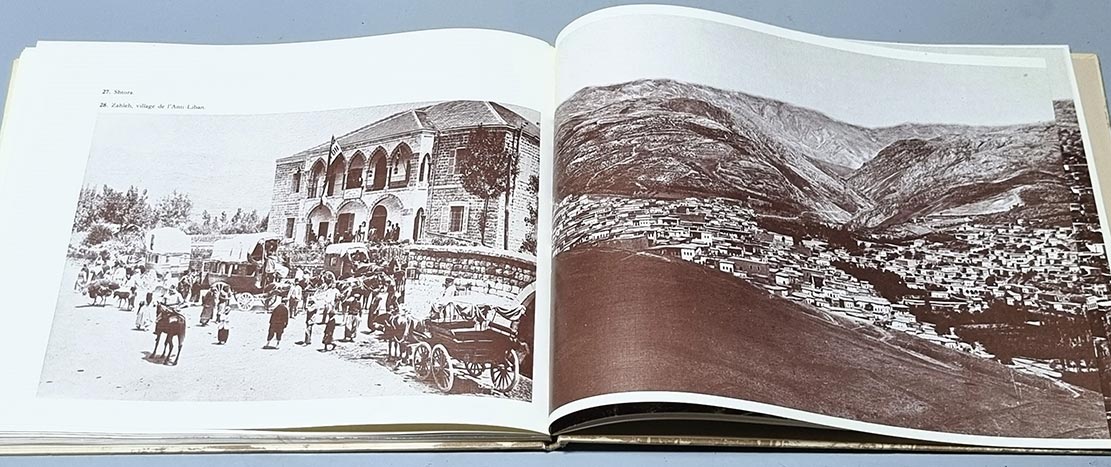

It is this mastery of exposure and printing methods which enables us today to enter into Bonfils’ pictures to wander through streets and fields, to inspect shop signs, the ornamental porches of villas, and the work of boatmakers, farmers, roof tilers, coachmen, educators, and entrepreneurs, to witness the industry of thousands of anonymous builders of modern Lebanon during a period when written records concentrate on transitory officials.

Humanly, the Bonfils became increasingly aware of their unique responsibility. As Félix’ son Adrien Bonfils (1861-1929) was to write on the eve of the 20th century:

“In this century of steam and electricity, everything is being transformed – even places… before progress has completely done its destructive job, before this present which is still the past has forever disappeared, we have tried, so to speak, to fix and immobilize it in a series of photographic views…”

Founded in 1889 ‘to promote sound knowledge of Semitic Languages and History’, the Harvard Semitic Museum presents these Bonfils photographs, with the assistance of colleagues throughout the world, to stimulate the search for other early visual records at this critical moment for Lebanon’s future and mankind’s.

Within Lebanon as well as in archives throughout the world, similar photographs must be found before it is too late and carefully preserved. As Beirut and other cities are rebuilt, forms of Lebanon’s environment, as it evolved through the centuries, should be studied and respected not anachronistically to impose the past as a burden on the future, but to proceed organically.

Spiritually as well, early photographs should enlighten humanity’s vision of Lebanon, counterbalancing recent devastation and perennial romantic fantasy with fresh visions of the talent and hard work of the Lebanese people in the cities, villages, and countryside of a century ago.

Several of the pictures shown here were made from almost the same vantage point of similar scenes, at different times. We have chosen to present such closely related photographs to encourage comparison and the practice of “photo archaeology.” Viewers should thus be able to freshly discover clues – perhaps of their own family’s activity as well as of Beirut’s vitality.

–

As rediscovered inheritance – a legacy in light of early photographs of Lebanon can now enrich and illuminate the future by saving forever visions of the past to inspire the work ahead.

LebanonPostcard will be responsible for sending the book you order, through a fast courier with a tracking number, guaranteeing reception of the package. The souvenirs may take between three and five days to arrive, according to the country they are sent to.

Additional information

| Weight | 1.0 kg |

|---|---|

| Dimensions | 1 × 1 × 1 cm |